“Infantile paralysis. No known treatment. Do the best you can with the symptoms presenting themselves.” – telegram to trainee bush nurse, Sister Elizabeth Kenny, in 1909.

By 1910, the doctor who sent this telegram was amazed to learn that she had treated six children with poliomyelitis, and none were crippled or deformed.

“I used what I had – water, heat, blankets and my own hands,” she said simply. But she would have to battle ridicule and the rejection of her methods, against the established wisdom of cruel immobilization.

She got scant support for her methods until 1933, and in 1940, after helping many children during a polio epidemic in Minneapolis, the US medical establishment also changed its tune, and the Sister Kenny Institute was opened there in 1942.

A Hollywood film portrayal followed in 1946, and by 1952, Sister Kenny was said to be one of the most popular women in America, second only to Eleanor Roosevelt.

Research

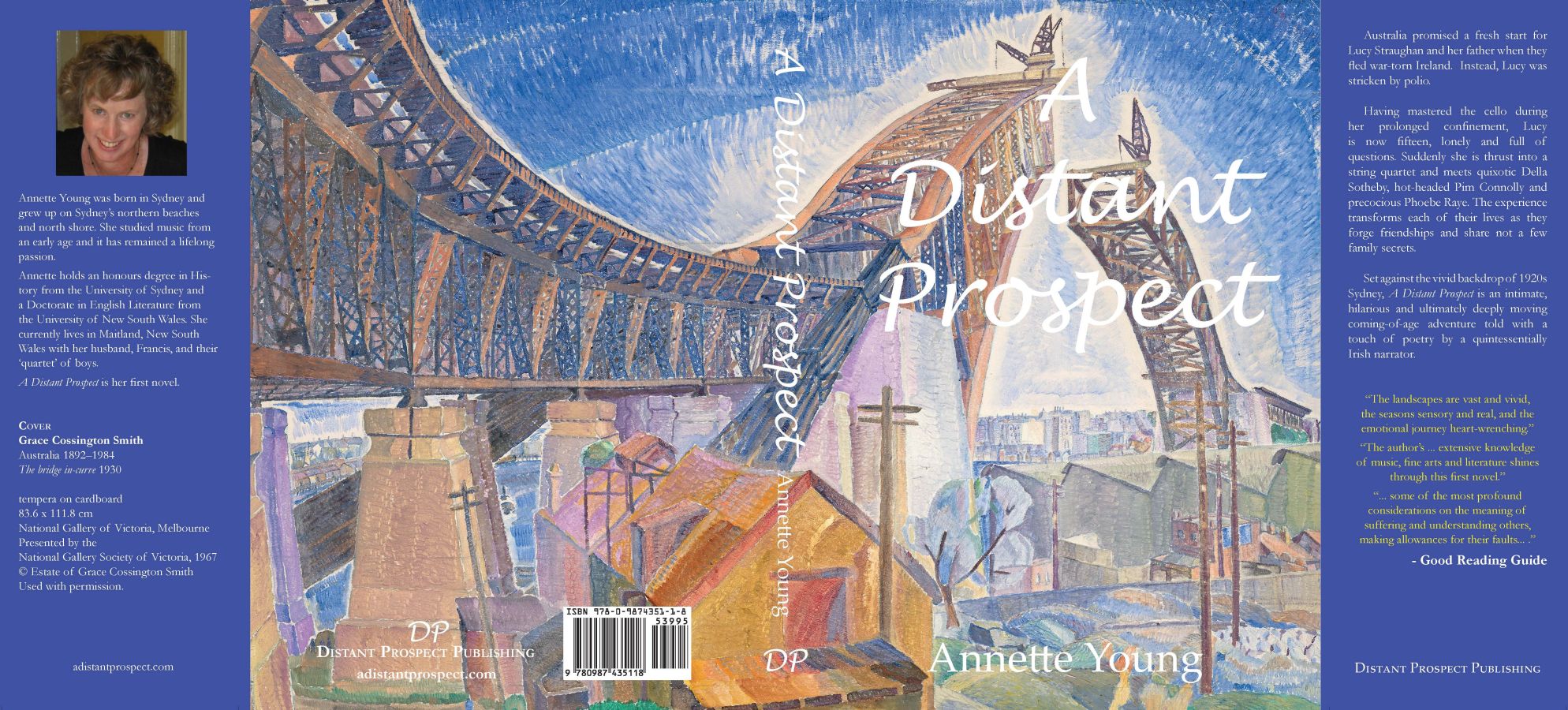

While researching early polio treatment for her fictional character Lucy in A Distant Prospect, Annette says it was hard to find much historic detail predating 1933. She did learn that unconventional muscular heat and movement therapy was successfully used on Sir Walter Scott as a child in the 18th Century. And that one of the worst aspects of polio, besides paralysis and deformed limbs, is the extreme pain, as recounted by Alan Marshall in his inspirational 1955 memoir, I Can Jump Puddles.

Annette was very gratified, at her Melbourne book launch, when a reader whose father had suffered polio commended her for describing so well the polio victim’s frustration and determination, as he had witnessed first hand.

Lucy’s suffering

After 8-year-old Lucy contracts polio while temporarily staying at the orphanage, her father Morgan Straughan wraps her legs in warmed woollen blankets, and works her limbs to move the muscles for her. (Sister Kenny would call this “reeducating” the muscles.) During Lucy’s visit to Moss Vale, Pim’s Aunt Rose instinctively takes a similar approach, soothing the pain and allowing her legs to make good improvement by the following day.

Still, Lucy’s pain and frustration sometimes verges on despair, as when she silently prays a Rosary with her Daid in Chapter 11:

What intentions did I have?

That God would make me walk properly again. That was a prayer half-answered. There I was, back on crutches, with braces on both my legs. Why, oh why was it so hard? Many a time I had been told that being crippled was God’s will and that I should accept it. So, the polio was the result of some divine prank was it? Well, if it was God’s will and God was all-powerful, why couldn’t He will it some other way? Would it matter to God that much if I could walk? But God did not seem to care whether I could walk or not.

That Mam would come back. Mam would never, ever come back. Mam had gone to God, or so I was told. But of what use was Mam to God when I needed her? I wanted her to hold me, I wanted to tell her everything that had happened; I wanted her to care for me. But God had taken her away and all that was left of Mam was locked up in the photographs and paintings that adorned our parlour walls.

I swung my beads all the harder.

God was not fair.

Finding out how Lucy will rise above these great sufferings of her life, and find new hope, continues to move readers to tears.