Dr Annette Young delivered a version of this text as a dinner speech for the Association of Australian Women Graduates at The Newcastle Club on 26 August 2015.

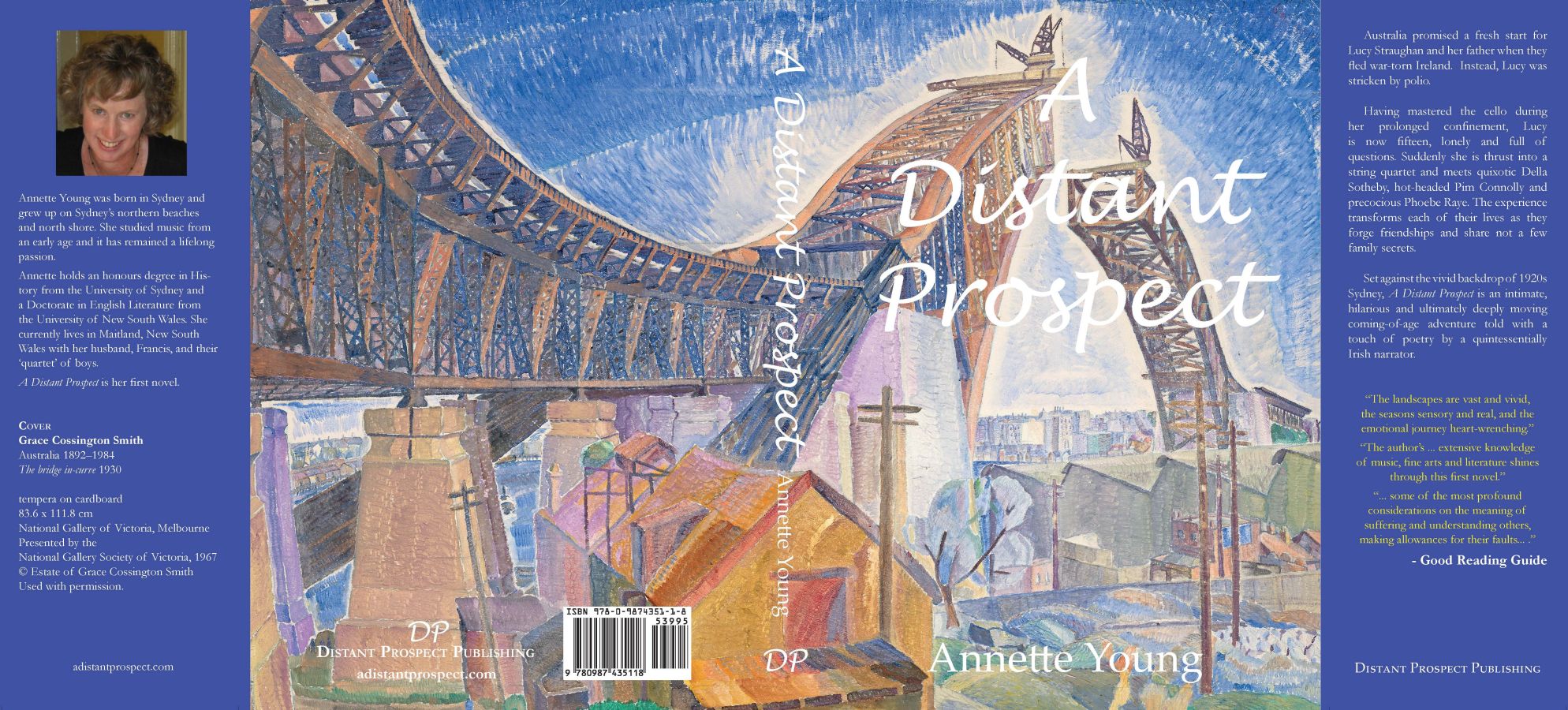

In the course of writing fiction, there comes a point when your story metamorphoses from being simply a story to being a book. In addition to the internal concerns of plot, character, and theme, the writer is faced with a new set of challenges. What will the title be? How should the cover look? How will the text be laid out? Will there be a dedication? Who do I need to thank? My husband and I often joke that A Distant Prospect was like our fifth child, for the process of turning the story into a book is like preparing for the arrival of a baby during which the excited parents deliberate over names, nursery decoration, nappies, and godparents.

Each of those choices has a story attached to it. But what I wanted to focus on in this piece was the book’s dedication. I dedicated A Distant Prospect to two women: my grandmother Lilias Yvonne Murray, who was born in 1906 and died in 1994; and my mother Margaret Lyne Cameron Nelson who was born in 1933 and is a wonderfully active eighty-two year old. My reasons for doing so were very simple: I was very attached to my grandmother; and her death, which was my first experience of the death of someone close; and my need to come to terms with that death, inspired me to write the book. Furthermore, I have always loved the nineteen-twenties – my grandmother’s era – and I wished to create a vignette of those times before first-hand knowledge of that increasingly remote age disappeared altogether. My mother was the person who listened patiently to every detail of the plot and was the first to be introduced to the book’s multiple characters. She read the early and later drafts, took an interest in the story and, I will admit that, while I don’t explicitly write people into my novels (it’s not fair), her caricature provided a model for one of the characters.

The Queen Mother with Princess Elizabeth and Princess Margaret, in a portrait by Sir Cecil Beaton

As far as worldly achievements are concerned, neither of these women is particularly exceptional. In many ways they are typical of their respective eras. Both enjoyed a sound, secure rural Tasmanian upbringing, and were moderately educated in keeping with the expectations of women at the time. They married in their early twenties, were devoted wives, conscientious mothers, and exceptionally skilled homemakers. My grandmother, a wonderfully optimistic, practical pint pot of a woman, modelled herself on the Queen Mother from top to toe – from her choice of hats and shoes to her easy grace and winsome smile. And she avidly read New Idea to keep up with the latest Queen Mother trend. My mother in some ways looked to our present Queen for an example, and to the dutiful, intelligent Elizabeth she added a touch of Grace Kelly glamour.

From a biographical perspective, it was quite natural to dedicate my first book to these two women. Yet it is also odd that two significant maternal figures should inspire a book in which absence of a mother figure is a key dimension of its plot, character and theme. One of the storylines of A Distant Prospect concerns the protagonist Lucy Straughan coming to terms with the loss of her mother, how her maturity stems from acceptance of that loss and how the wisdom acquired from that experience enables her to help others. Writing, however, is quite extraordinary with regard to what it reveals of the author’s subconscious. As a writer, the first awareness of this is quite confronting, and can be life changing – it was in my case. In the search for metaphysical, emotional and moral truths you probe the depths of your own character and experience in ways you never anticipated. I did this many times in the course of writing A Distant Prospect; and now that I am writing a second novel, I am doing it all over again, to the point that I am becoming quite accustomed to it. I even relish the activity.

To return to my original point, why did I dedicate a novel without a mother to two mothers? Typical of the writer, I indulged in a long spell of navel-gazing to discern whether there was some deeply personal significance. After all, the only reliable source of experience is one’s own. So the best place to begin with is oneself.

While my grandmother was a woman of the Jazz age and the Depression – each in their own way prodigals of the Edwardian Era and the First World War – and my mother very much a woman of the Brave New World of the 1950s, I am a child of the 1960s – certainly not the psychedelic flower power, all you need is love, ‘Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds’ aspect of those years – those elements while they were at large in 1960s Avalon, where I spent my early childhood (my mother went through a phase of wearing caftans, hotpants, and a Sonya McMahon evening dress which she toned down with the addition of zippers in the side seams; Mr Whippy did drugs at Barrenjoey High; a de facto couple lived in the new hacienda inspired construction, and hippie surfies lived in a cave on my best friend’s property), they never quite made it into our living room. What was welcomed, however, was Women’s Liberation. Again, it was not a virulent burn the bra Feminism – my mother was way too prudent – but Women’s Lib became a regular house guest, and I have memories of my mother standing up to my father, daring not to take his opinion, defending her rights to what really was respect, and insisting upon some form of financial independence. Male chauvinist pig was a term with which I was familiar by the age of ten; and my mother’s ideas, along with more strident attitudes and more clearly enunciated expectations, were reinforced by the Methodist girls’ school I attended in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

At school, the teachers expected that we would pursue a career. This may not have been the case for everyone, but it was certainly assumed that career would be the paramount decision of the girls in the higher classes. Marriage was second rate: the choice of those who didn’t have the brains for the professional world. The active promotion of certain forms of birth control by teachers during personal development classes in later high school years carried the assumptions that we were more likely than not to have sex outside marriage, and that children were to be avoided rather than encouraged. I left school with very mixed ideas: my home life was neither unhappy, nor particularly happy. I was witness to two people struggling to make a marriage work and raising well-educated children while maintaining a healthy level of social approval on Sydney’s North Shore. But I disliked what my mother had to put up with; I strongly disliked my mother’s concerted efforts to keep up appearances (social and otherwise); and I had a hearty distaste for school. What was uppermost in my thoughts, however, was a strong determination to pursue a career and not to marry.

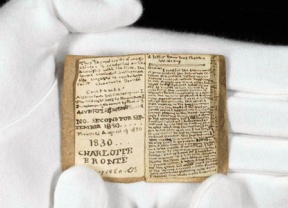

Like Miles Franklin, I can say with some irony now: my brilliant career. I desired to be an artist, a sort of Renaissance Woman of Arts and Letters. But the dreams of one’s youth collide with the reality of the outside world, for which a north shore upbringing and private girls school education renders you quite ill-prepared. As with Hamlet, outside influences, personalities, expectations and manipulations had a crushing existential effect upon me. My initial ambition was the theatre. However, I did not like acting, for I did not like the roles I had to play as a woman and a small young woman at that. As a result, I knew I had to arm my intellect to the hilt, because my body rendered me vulnerable. Instead, I turned my interests towards costume and set design, direction, and music. I never intended to be a writer, even though in many ways writing came very naturally to me. From the arts, I entered brief teaching stint, imbued with guilt that those who can do, those who can’t teach. From teaching, I entered academia in an increasingly introverted quest for intellectual and emotional fulfilment. And it was from the cerebral precipice of PhD research that I fell into writing. While working on manuscripts of Charlotte Brontë – herself a woman who was for the most part self-educated and determined to make her mark on the world – I gained an insight into the workings of a writer’s mind, and decided to apply myself to the art and craft of literature. I wrote what became the first draft of A Distant Prospect fifteen years ago. Primarily, it was a test of literary theory. And it is safe to say that I wrote it as a professional, heading on a new career path as an academic after five years of teaching and in the midst of a personal crisis – the sort one has when they turn thirty and realise to their horror that they are not yet famous.

Like Miles Franklin, I can say with some irony now: my brilliant career. I desired to be an artist, a sort of Renaissance Woman of Arts and Letters. But the dreams of one’s youth collide with the reality of the outside world, for which a north shore upbringing and private girls school education renders you quite ill-prepared. As with Hamlet, outside influences, personalities, expectations and manipulations had a crushing existential effect upon me. My initial ambition was the theatre. However, I did not like acting, for I did not like the roles I had to play as a woman and a small young woman at that. As a result, I knew I had to arm my intellect to the hilt, because my body rendered me vulnerable. Instead, I turned my interests towards costume and set design, direction, and music. I never intended to be a writer, even though in many ways writing came very naturally to me. From the arts, I entered brief teaching stint, imbued with guilt that those who can do, those who can’t teach. From teaching, I entered academia in an increasingly introverted quest for intellectual and emotional fulfilment. And it was from the cerebral precipice of PhD research that I fell into writing. While working on manuscripts of Charlotte Brontë – herself a woman who was for the most part self-educated and determined to make her mark on the world – I gained an insight into the workings of a writer’s mind, and decided to apply myself to the art and craft of literature. I wrote what became the first draft of A Distant Prospect fifteen years ago. Primarily, it was a test of literary theory. And it is safe to say that I wrote it as a professional, heading on a new career path as an academic after five years of teaching and in the midst of a personal crisis – the sort one has when they turn thirty and realise to their horror that they are not yet famous.

As I mentioned earlier, writing is confronting. In writing a novel, I did not expect to face what I had suppressed for most of my childhood and adult life. I recognised my depression, a depression caused by emotional suppression, by denial of or fear of my own womanliness, which caused me to retreat into the world of the intellect as a means of protection, much of which I unwittingly worked into my protagonist Lucy Straughan. I had rejected love. I can remember quite distinctly after writing the book realising that I could no longer love an abstraction – that I could not survive through living in the world of ideas.

Lucy’s path to spiritual and emotional wholeness is opened largely by the loving affection of a mother. Many readers have told me that one of their most favourite characters in the book is Aunt Rose. She is a young woman, with a young family, who lives on a farm worked by her husband who during the War had served with the Light Horse at Beersheba. She is a woman of my grandmother’s generation: homely, hardworking, and devoted to her husband and children – with the added sobering experience of having worked as a nurse on the Western Front. People ask me where she came from. Well, she is partly my grandmother, partly my mother, and strangely also an idealised version of myself, when as a child I used to imagine the mother I would like to be. For Lucy, and I suppose for me also, she is the epitome of everything a mother could or should be: a comforting, enriching presence.

Unlike almost every other character, Aunt Rose remains virtually unchanged in both versions of the novel; for I should add now that I rewrote A Distant Prospect after fifteen years. The novel I first scribbled down as a burgeoning academic was rewritten by a woman who, in addition to holding a PhD, had become a wife and a mother of four small boys (although they’re not quite so small now and would be most indignant to hear themselves being described in this way). While my academic training was certainly of great assistance in reworking the book, there is nothing quite like marriage and childbirth, husband and family to hone one’s craft, particularly when it comes to writing about human relationships.

This brings me to consider the works of some of my favourite women authors. While I admire and enjoy the novels of Jane Austen and Charlotte Brontë, their study of character, their empathy and compassion, and in some ways the depth and long-term satisfaction of their writing, pale in comparison to the like of Elizabeth Gaskell and George Eliot. Austen and Brontë, writing as single women, were gifted observers, but they are outsiders regarding the world of intimate human relations. In fact, they employ their narrative skills in the creation of outsider types. Elizabeth Bennett with her independent views is a spirited outsider in her preparedness to uphold her personal conviction to marry for love and not for the sake of social norms. Fanny Price in Mansfield Park is a more introverted version of a woman with sound judgment, emotional depth, and moral integrity who is isolated by her less fortunate social circumstances. Jane Eyre and Lucy Snowe are classic representatives of marginalised women in Victorian society, forced by circumstance to make their own way through life. Whilst Austen and Brontë’s novels contain memorable depictions of their heroines and their emotional worlds, they are frequently judgemental and disparaging towards weaker or apparently less than desirable characters. I would not like to fall foul of Jane or Charlotte. Their works have a moral to preach and they do so powerfully. In both cases, love and marriage are paramount concerns. Brontë’s fervent appreciation of the dignity of the human person derived from their god-given individuality and not from their social standing, their appearance, or even their virtue; the human capacity for love, and the need for happiness based on love, is her most enduring theme. Austen imparts sound advice to her generation (and indeed to future generations) on the importance of a wise choice of life partner.

This brings me to consider the works of some of my favourite women authors. While I admire and enjoy the novels of Jane Austen and Charlotte Brontë, their study of character, their empathy and compassion, and in some ways the depth and long-term satisfaction of their writing, pale in comparison to the like of Elizabeth Gaskell and George Eliot. Austen and Brontë, writing as single women, were gifted observers, but they are outsiders regarding the world of intimate human relations. In fact, they employ their narrative skills in the creation of outsider types. Elizabeth Bennett with her independent views is a spirited outsider in her preparedness to uphold her personal conviction to marry for love and not for the sake of social norms. Fanny Price in Mansfield Park is a more introverted version of a woman with sound judgment, emotional depth, and moral integrity who is isolated by her less fortunate social circumstances. Jane Eyre and Lucy Snowe are classic representatives of marginalised women in Victorian society, forced by circumstance to make their own way through life. Whilst Austen and Brontë’s novels contain memorable depictions of their heroines and their emotional worlds, they are frequently judgemental and disparaging towards weaker or apparently less than desirable characters. I would not like to fall foul of Jane or Charlotte. Their works have a moral to preach and they do so powerfully. In both cases, love and marriage are paramount concerns. Brontë’s fervent appreciation of the dignity of the human person derived from their god-given individuality and not from their social standing, their appearance, or even their virtue; the human capacity for love, and the need for happiness based on love, is her most enduring theme. Austen imparts sound advice to her generation (and indeed to future generations) on the importance of a wise choice of life partner.  Gaskell and Eliot on the other hand, were mothers writing for their children. Like Brontë and Austen, their novels have a moral purpose, but it is accompanied by insight and tenderness, softened by understanding and acceptance of human foible. Middlemarch has a richness and depth for which I have so much respect that I am still savouring it after first reading it as an undergraduate. Certainly, Lizzie Bennett and Fitzwilliam Darcy dazzle and entertain, but the plight of Dorothea Brooke, the coldness of Casaubon, and the passion of Will Ladislaw penetrate deep into the heart and mind.

Gaskell and Eliot on the other hand, were mothers writing for their children. Like Brontë and Austen, their novels have a moral purpose, but it is accompanied by insight and tenderness, softened by understanding and acceptance of human foible. Middlemarch has a richness and depth for which I have so much respect that I am still savouring it after first reading it as an undergraduate. Certainly, Lizzie Bennett and Fitzwilliam Darcy dazzle and entertain, but the plight of Dorothea Brooke, the coldness of Casaubon, and the passion of Will Ladislaw penetrate deep into the heart and mind.

With these thoughts in mind, I would like to reflect on the value of mothers. Mothers have a special insight gained from intimate love and the bearing and raising of children which is vitally important to consider while we are in the thick of the same-sex marriage debate, income tax reform, and family law. And here we see where women’s liberation has utterly failed. Women certainly enjoy more opportunity to pursue careers than they did decades ago, but mothers remain as downtrodden and devalued today as we were led to believe they were some thirty years ago, when Women’s Liberation sought to cut the apron strings in the name of ‘equal rights and equal opportunities’. Forgive me for my cynicism but mothers enjoy some status as the driver of cars doing the rounds for her children after school, or putting a Masterfoods meal on the table. But overall it is expected that the mother works outside the home as well as in it. Never was she under so much pressure to maintain a job and manage a home and family. Mothers who choose to stay exclusively at home and dedicate themselves to their families lead a cloistered existence, with brief periods of liberation in coffee shops, school pick up lines, and supermarkets. My ninety-four year old neighbour recalls the time when the street was full of families. ‘We helped each other out,’ she says. That’s all gone. Everyone’s out to work by eight, home at six for an exhausted few hours to push through homework, dinner, and family time (if any) before crawling into bed, only to face more of the same the following day. Society delights in parodies of desperate housewives; anthropological studies have been made on New York’s executive wives. I know from personal experience that I gain considerable advantage when I use my title ‘Dr’ in medical situations because ‘Mrs’ is viewed rather superciliously by the experts. In government policy regarding taxation and child benefits, we see a shift in favour of two income households; while in the divorce courts the role of ‘mother’ is maliciously wielded by the woman to her advantage.

What is left of the beauty and value of motherhood; of the preciousness of marriage and childbirth? The mystery, beauty and reality of the human family, with its foundation on love in its many facets: intellectual, physical, emotional? Increasingly, society equates love with personal satisfaction rather self-giving. Even the meaning of sacrifice is tainted with pharisaical egoism as the media parades heroic stories before the public. Much talk of love is linked with sexual identity: again the imposition of the ego – the ‘I’ and its so-called rights. There is little consideration of love and responsibility. Motherhood remains as unassuming and taken for granted as it was generations ago. But the woman who cares for others, whose identity is bound up in her children, her home, in her love for her husband, is not without character or integrity. She is much enriched by her self-giving. Nor is her role without significance: A mother holds the past the present and the future in her hands. Motherhood is difficult, tiring, demanding, unfair. I know it well as I myself try to juggle motherhood with my intellectual and creative work, and I am fortunate enough to work from home. Trying to write this piece was a major feat. And now I’m trying to write another book. At the same time I feel the legacy of Gaskell and Eliot: My motherhood is the oxygen that enlivens the fire of my creativity; my professional training provides the sticks and the many crumpled sheets of paper that are thrown on it. My children do not exist in opposition to this work. On the contrary, they are inspirational, humanity in the raw, and they like to be involved, so long as they know they come first. ‘Tell me about your book,’ my sensitive nine year old will often ask. How do I do it? Once again I take inspiration from my grandmother: rise early, housework done by eleven, with private work – creative activities, visiting etc – saved for the afternoon.

What is left of the beauty and value of motherhood; of the preciousness of marriage and childbirth? The mystery, beauty and reality of the human family, with its foundation on love in its many facets: intellectual, physical, emotional? Increasingly, society equates love with personal satisfaction rather self-giving. Even the meaning of sacrifice is tainted with pharisaical egoism as the media parades heroic stories before the public. Much talk of love is linked with sexual identity: again the imposition of the ego – the ‘I’ and its so-called rights. There is little consideration of love and responsibility. Motherhood remains as unassuming and taken for granted as it was generations ago. But the woman who cares for others, whose identity is bound up in her children, her home, in her love for her husband, is not without character or integrity. She is much enriched by her self-giving. Nor is her role without significance: A mother holds the past the present and the future in her hands. Motherhood is difficult, tiring, demanding, unfair. I know it well as I myself try to juggle motherhood with my intellectual and creative work, and I am fortunate enough to work from home. Trying to write this piece was a major feat. And now I’m trying to write another book. At the same time I feel the legacy of Gaskell and Eliot: My motherhood is the oxygen that enlivens the fire of my creativity; my professional training provides the sticks and the many crumpled sheets of paper that are thrown on it. My children do not exist in opposition to this work. On the contrary, they are inspirational, humanity in the raw, and they like to be involved, so long as they know they come first. ‘Tell me about your book,’ my sensitive nine year old will often ask. How do I do it? Once again I take inspiration from my grandmother: rise early, housework done by eleven, with private work – creative activities, visiting etc – saved for the afternoon.

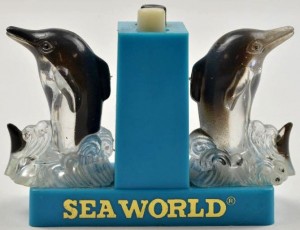

After my grandmother’s funeral our family gathered at her old home. In the centre of her kitchen table was a set of plastic saltshaker dolphins. My brother and I looked at them and grimaced. Yet another piece of tacky grandmother kitsch like the crochet toilet roll dollies and the posters of cutsie kittens. But there is a story attached to those dolphins. We were staying at Surfer’s Paradise. I was eleven at the time, and I had five dollars to spend in a souvenir shop at Sea World. I made the decision to buy something, not for myself, but for Gran. I thought the saltshaker dolphins were perfect. And they were practical, too, unlike those shell-decorated trinkets and ornaments which filled most of the shelves in the store.

After my grandmother’s funeral our family gathered at her old home. In the centre of her kitchen table was a set of plastic saltshaker dolphins. My brother and I looked at them and grimaced. Yet another piece of tacky grandmother kitsch like the crochet toilet roll dollies and the posters of cutsie kittens. But there is a story attached to those dolphins. We were staying at Surfer’s Paradise. I was eleven at the time, and I had five dollars to spend in a souvenir shop at Sea World. I made the decision to buy something, not for myself, but for Gran. I thought the saltshaker dolphins were perfect. And they were practical, too, unlike those shell-decorated trinkets and ornaments which filled most of the shelves in the store.

My grandmother’s saltshaker dolphins say a lot: Regardless of what Gran thought of my personal taste, she knew the value of the gift – the connection between the gift and the giver. Twenty years later, those saltshaker dolphins still held special place on her kitchen table because Gran treasured me. That’s motherhood. Anyone else would dismiss the plastic saltshaker dolphins from Surfers Paradise as a piece of worthless kitsch (as I did some twenty years later until my conscience pulled me up). A mother looks further and sees a pearl without price that is love.

Dr Annette Young is the mother of four boys, and author of 1920s novel A Distant Prospect (2012) and its forthcoming wartime sequel, In The Hearts of Kings (2017). Her author website is http://annetteyoung.net

This article was published in October 2015 on the St Austin Review blog,edited by Joseph Pearce.