One of the challenges of By Violence Unavenged has been make the world of 1930s Vienna accessible to a non-German speaking reader. Music, and song in particular, has proved an invaluable medium. Austrians love to sing, so the inclusion of song is essential in bringing that culture to life. By Violence Unavenged abounds in songs: lieder, Wienerlieder, anthems, hymns, marching songs, Christmas carols, and music hall ditties. And, no, there is no singing of ‘Eidelweiss’. Some are in the original German, others translated; and I suppose there are going to be quite a lot of endnotes.

Sometimes, however, a song is a useful tool for creating atmosphere and presenting themes, but is dramatically inappropriate. For instance, having a seven year old non-German speaker sing Schubert’s ‘An Die Musik’ in perfect German would be out of place, pretentious, and boring from a dramatic perspective. But, for a seven year old to sing a mondegreen version of the song, now that works!

The Death of Lady Mondegreen

A mondegreen is a mishearing or misinterpretation of a phrase resulting from the mishearing of a poem or song, in a way that gives it a new meaning. The term was coined in 1954 by American writer Sylvia Wright when recalling how as a girl she had misheard the lyric “…and laid him on the green” in a Scottish ballad as “…and Lady Mondegreen” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mondegreen).

Children are brilliant at this form of linguistic corruption. They frequently convert the sounds they hear into words they comprehend and warp the meaning in the process. In the Australian National Anthem, for example, youngsters will patriotically sing ‘Australians all eat ostriches’, instead of ‘Australians all let us rejoice’. One can only wonder what is going on in their heads.

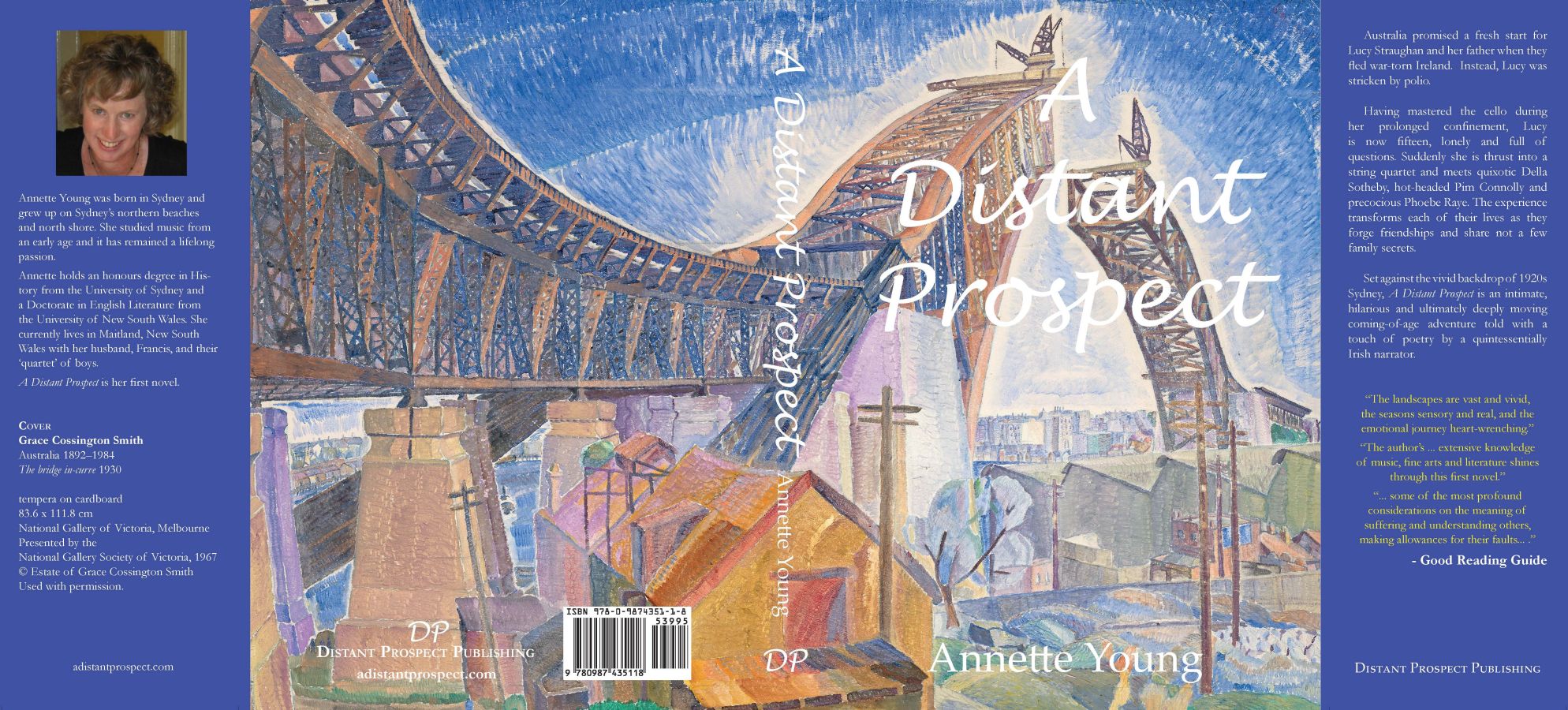

In By Violence Unavenged, a seven year old Phoebe Raye sings her own mondegreen version of Schubert’s ‘An Die Musik’ based on what she has heard of the original German lyrics sung by her father. For the author, it was a fun piece of writing, the result of repeated listening to Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. For young Phoebe, ‘An Die Musik’ is ‘Handy Music’. This form of corruption, in which music is twisted (innocently and rather humorously in the above instance) prefaces the use of music in In the Hearts of Kings, in which music becomes a very ‘handy’ tool. Whereas in the post World War I world of A Distant Prospect, music restores and heals; in Hearts of Kings music might be a thing of beauty, an ambassador from ‘a better world’, but it is also a means of propaganda and defiance; it might heal, but it is also a poison; it is both creative and destructive; finally, it is critical to survival. As such it reflects the disturbed brave new world of a Europe heading towards another, even more catastrophic war; as well as the conflicted inner world of of the protagonist herself.