What are the origins of the Dawn Service tradition, and why does it matter?

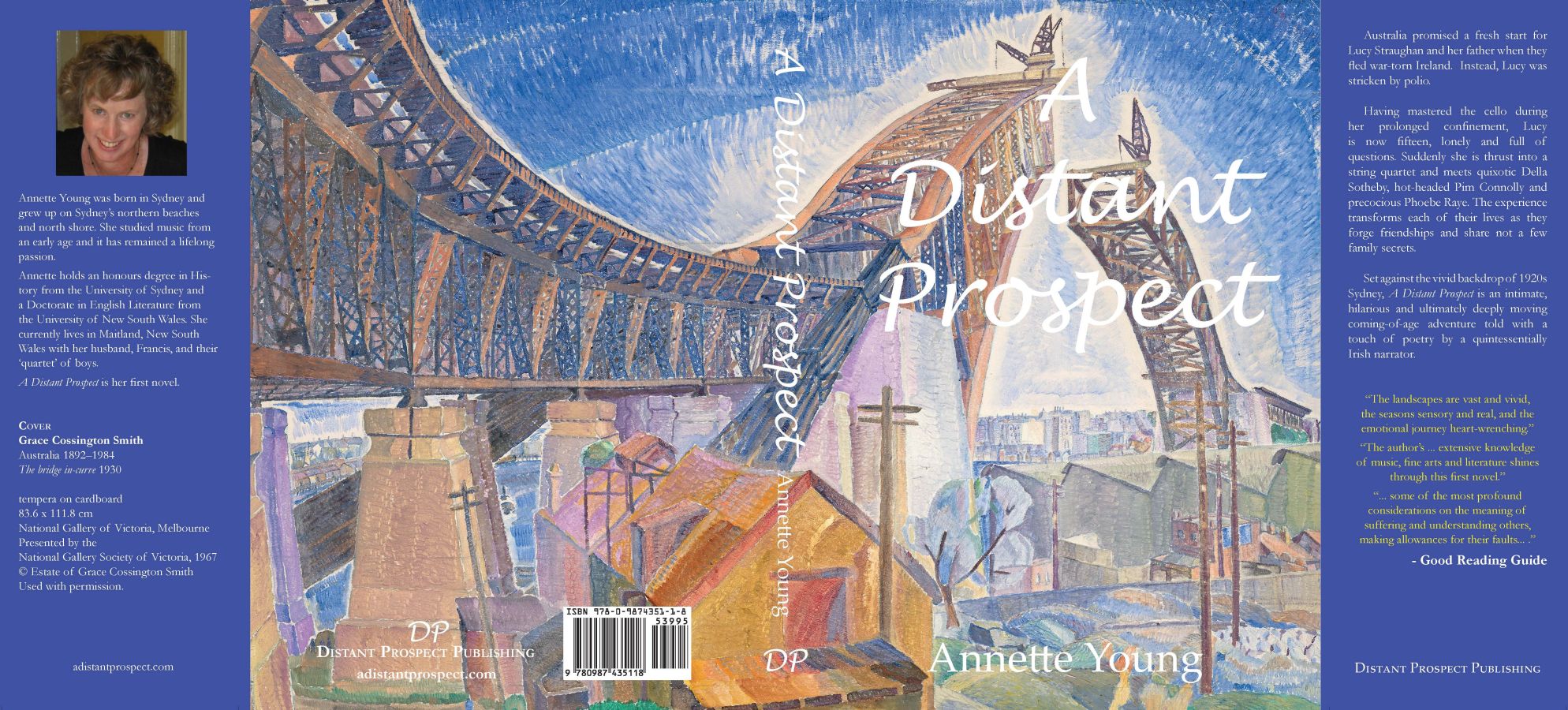

Wreaths on the Cenotaph, Martin Place, Sydney,

Anzac Day, 25 April 1930 / photographer Sam Hood

(State Library of NSW collections,

no known copyright restrictions)

Few were left unscathed by the Great War. We still witness many of its lasting impacts in the 1928 Sydney setting of A Distant Prospect. Indeed, the very first Dawn Service was quietly held in Sydney in 1928. It is a fitting, universal and sober commemoration of sacrifices made, and not a show of jingoism, militarism, or nationalism.

Australia had only recently federated in 1901 and was still very much part of the British Empire. When Belgium was invaded in 1914, Great Britain went to war, and so did Australia and New Zealand.

The Anzac expedition was ostensibly to support British attempts to take the Dardanelles and reduce Turkey’s usefulness to the German enemy. The follies of the failed campaign are well documented, including inaccurate 1854 terrain maps, futile battle charges, and not withdrawing sooner. But the Gallipoli landings on 25 April 1915 marked the first time Australian and New Zealand lives were put on the line on the world stage.

Pausing on 25 April allows us to consider the sacrifice made by so many Australians in defence of freedom and higher values, and the suffering and loss of their families, even while acknowledging that wars are not always justly waged, and that valour and righteousness may be found in the ranks of all nations at different times.

Anzac Day had been officially marked with military parades since its first anniversary in 1916, often to promote recruiting and patriotism for the cause. The Dawn Service is not a military event, but rather a public ceremony offered by returned soldiers.

Origins

Just before dawn on the battlefield, soldiers were often quietly awakened to “stand-to”, ready to launch or repel an attack at first light. Soldiers gathering in the pre-dawn quiet experienced comradeship, self-recollection, and thoughts of distant loved ones and fallen comrades. These were dark, silent, prayerful moments.

The Australian War Memorial notes:

In 1927 a group of returned men, returning from an Anzac Day function held the night before, came upon an elderly woman laying flowers at the as yet unfinished Sydney Cenotaph at dawn. Joining her in this private remembrance, the men later resolved to institute a dawn service the following year. Thus, 150 people gathered at the Cenotaph in 1928 for a wreath laying and two minutes’ silence. This is generally regarded as the beginning of organized dawn services.

We do well to ignore the inevitable superficial commercial intrusions, just as we should at Easter, Christmas and Hallowe’en (All Hallows Eve).

Solemnly contemplating the great love of giving up one’s life for a higher good is part of our common humanity. Even as we pray for peace, we should not forget those who fell.

The Anzac Day Dawn Service is a quiet, universally relevant remembrance of sacrifice, heroism, and loss. Lest We Forget.